Editor’s note: Our “Unpacking” Series provides a deeper look into the ideas of Clarity, one of JumpRope’s Core Values.

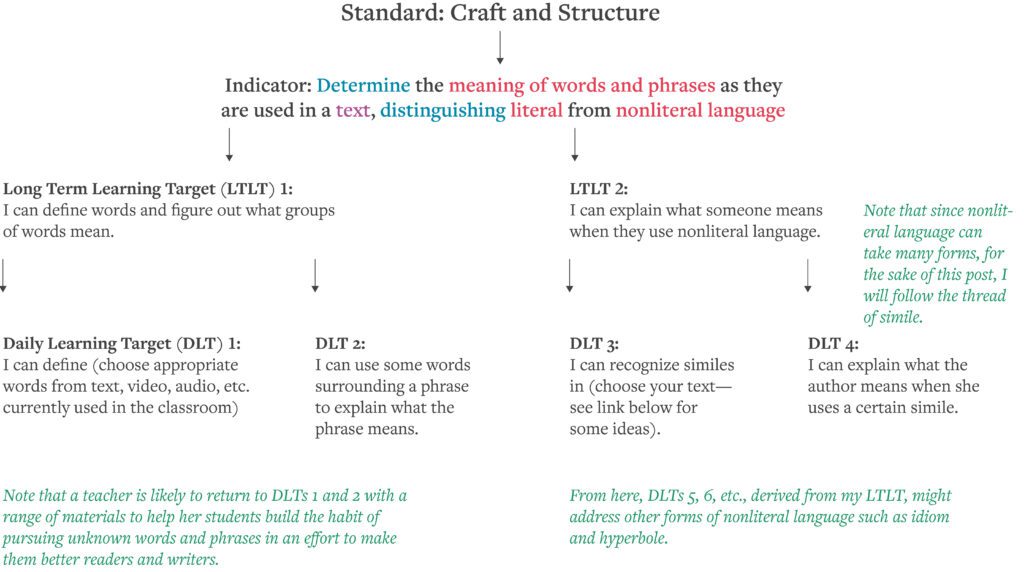

In an effort to provide our readers with multiple perspectives, this post offers a look at how other authors might unpack standards to create actionable instructional and assessment targets. Moving from Standards to Learning Targets focused on the process I use to develop clear and actionable classroom-based learning and assessment targets. I referenced this graphic which uses a third grade CCSS in literacy as an example of how I move from a set of national standards to planning for clear daily instruction and assessment. The graphic demonstrates how I categorize learning goals in three ways: Indicator, Long Term Learning Target (LTLT) and Daily Learning Target (DLT). This phrasing works well for my students and me, but there is nothing sacred about it, so you should use phrasing that feels right for your students and you. You might also take inspiration from the good ideas others share as they discuss their approach to breaking down the standards.

Reference: Teaching Similes and Metaphors

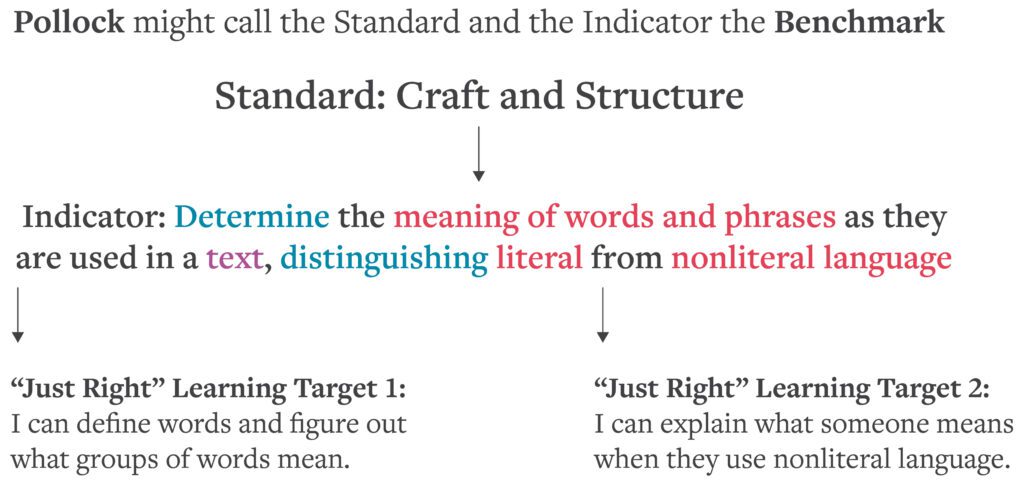

Back in 2007, Jane Pollock told us that the foundation of the well-articulated curriculum is what she calls the “learning target” (28). The learning target, as she describes, is the unpacked version of the benchmark or standard, the articulation of the central concepts, skills, and information students are meant to grasp. She advocates for teachers to use “Just Right” learning targets. These rest somewhere between acquisition of factual knowledge (name, list, identify) and the “kitchen sink model” or our broadest aims (read, write, and speak…) Pollock provided one of my first formal introductions to the idea of deconstructing a benchmark or standard and thinking about it at different levels. While she doesn’t use the same verbiage I do, it might be helpful to consider this graphic as a way to think about learning targets through a Jane Pollock lens.

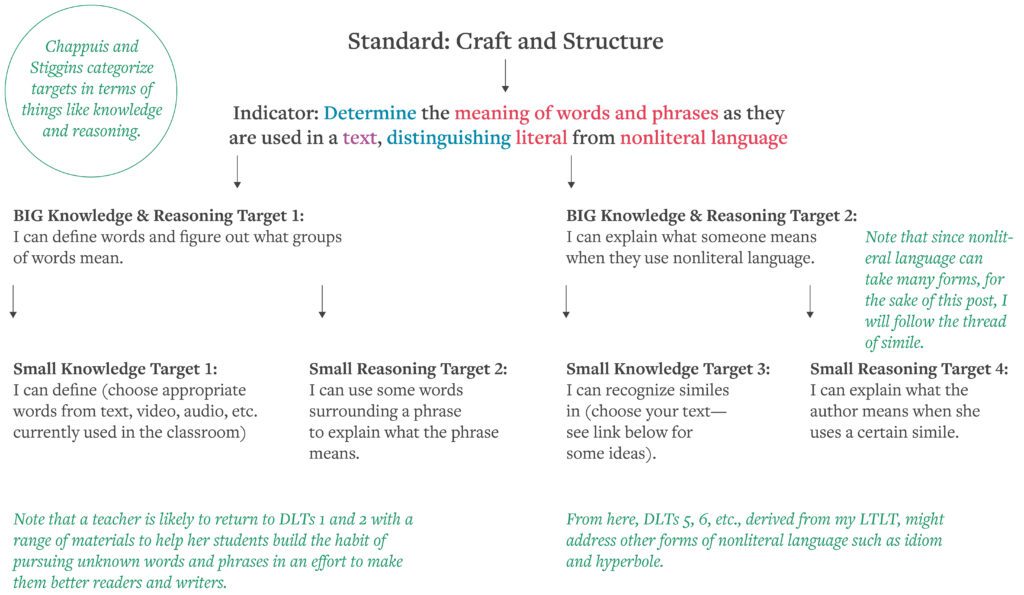

As I read more literature on learning targets, I found different ideas of what Pollock calls the “Just Right” target; a target whose size promotes its accessibility for teaching and learning. In moving toward accessibility, Chappuis and Stiggins categorize learning targets for us. Beyond considering what students should learn, they look at the writing of targets in terms of how students learn and what we ask them to do in order to learn. In An Introduction to Student-Involved Assessment for Learning, they name knowledge, reasoning, performance, product, and disposition as categories for learning targets (47). This system of sorting builds on Pollock’s ideas. It honors the fact that sometimes our daily targets need to focus on factual information (I can recognize similes) as we help students build toward higher level thinking (I can explain what the author means when she uses a certain simile.) Some of that higher order thinking includes things like reasoning and the creation of products such as research papers. Below is a Chappuis Stiggins graphic to help visualize their categorization. Chappuis and Stiggins therefore help us see that categorizing our targets helps students see what they need to learn and how they will learn it.

Reference: Teaching Similes and Metaphors

I see a similar categorization in the work of Rinkema and Williams, only they are thinking at a level broader than the daily learning target. They tell us, “Making sure our targets are set to the appropriate scope provides the motivation necessary to continue pushing toward more rigorous learning.” (27) They go on to name and describe three scopes, noting that some educators refer to scope as “grain size”. They speak to yearlong targets, those which will genuinely require a full year of instruction for a student to attain. Next is repeating targets, those that are addressed over and over again in instruction and possibly even across content areas. Finally, they speak to unit targets, those we address through a discrete unit of study and would therefore not return to at a later date. Below are examples of each from their work. They sort the learning in a fashion similar to Pollock and Stiggins and Chappuis by speaking to what they intend for their students to know, understand and be able to do (KUD).

EXAMPLE YEARLONG TARGET

I establish and maintain a clear purpose in my writing through a thesis and leads, the choices I make in the body, and my conclusion; my purpose is appropriate to my audience and to the assignment and stays consistent throughout my writing. (28)

EXAMPLE REPEATING TARGET

I have a clear aim with multiple relational ideas; the claim requires varied evidence and substantive analysis to prove. (28)

EXAMPLE UNIT TARGET

I can analyze how an author uses rhetoric to advance a specific point of view or purpose in a text. (29)

One additional way to consider learning targets comes from the research done by my USM colleagues, Anita Stewart McCafferty and Jeff Beaudry. They write about learning targets in terms of Stars and Stairs, a visual progression of sequential steps, each topped with a star to note attainment of that particular step. Here is a Kindergarten example of a Stars and Stairs progression. Here is a middle school example of a Stars and Stairs progression. Each step in the sequential staircase provides students with the appropriate “I can” statement for them to work on. The steps within a staircase could contain learning that is factual or knowledge-based, conceptual or reasoning/understanding-based, procedural or skill-based, or product- or dispositions-based. It seems reasonable to think that teachers would create different staircases for each of those types of learning.

I believe students will learn more and learn better if we point out our learning goals, help them know what the goals mean, and help them see clear pathways to attaining the goals.

There are lots of different ways to think about, categorize, and even use learning targets. I’m partial to each of the authors I mention above and dedicated to the idea that each teacher finds the conception of figuring out and naming learning and assessment goals that best suit her students and her. I am convinced, though, that once each of us finds that conception, it is imperative that we illuminate it for our students. I believe students will learn more and learn better if we point out our learning goals, help them know what the goals mean, and help them see clear pathways to attaining the goals. Coming soon, I’ll explore the idea of talking about learning goals with students. I’ll look at when, and what to say and revisit why all of that is so important.