This post provides a deeper look into the ideas of Clarity and Equity of Opportunity, two of JumpRope’s Core Values.

Have you ever read through a stack of student assessments and realized that one or more of the questions or prompts you used was somehow “off”? Designing assessments is no easy task, especially performance tasks and those that ask students to create products. As I described in Why and How to Use Rubrics, the first step is to figure out what the students are supposed to learn. On its face, that’s not too hard to do, but once we begin to create all the tools we’ll use to assess that learning, it’s easy to go astray.

Ensuring all the assessment tools we create for any particular assessment experience actually do what they are intended to do is another way of saying they are valid. Checking our tools for validity is an important step toward clarity and equity of opportunity.

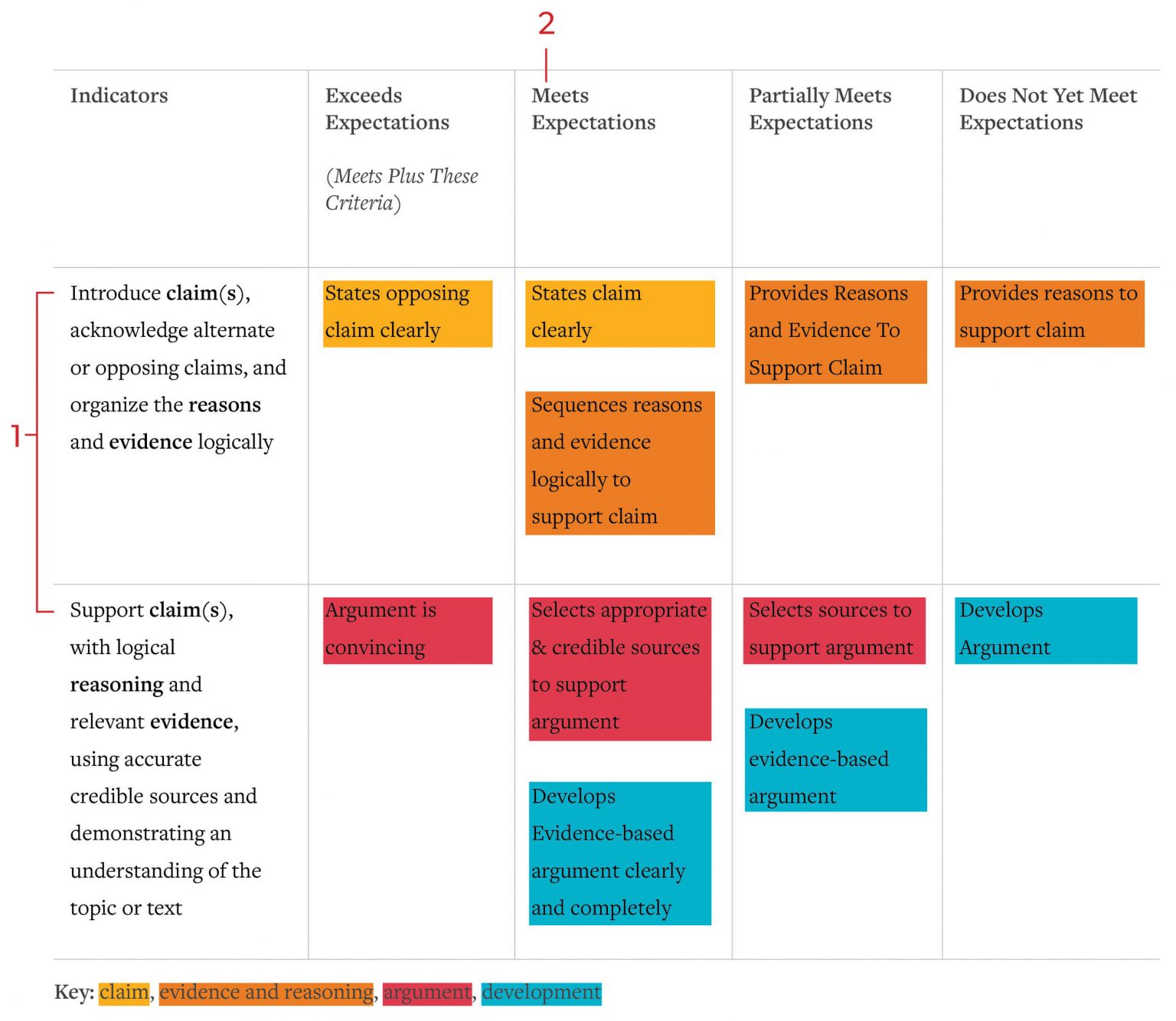

In examining the idea of validity, we see that it has several components. The most straight-forward component is construct validity. To test construct validity, we would ask, “Does this assessment measure what it is supposed to measure? Does it reflect what we have studied on this topic? Do the tools I am using to guide the assessment, like the product descriptor and rubric, align with one another?” In my own practice, I check this by comparing the long term learning targets and performance indicators I have used instructionally to the tools I have created for assessment. I also compare those assessment tools to one another, cross-checking to be sure the things I prompt for in the directions are the same things I evaluate as I read student work. This concept is critical when we design multiple tools to support an assessment, as in the cases of performance assessment and product creation. Imagine a set of tools you create to correspond to the rubric referenced in Why and How to Use Rubrics, pictured below. You might design a graphic organizer, a check sheet, and a directions page. It is imperative that all the prompting language in those tools is parallel to the language on the rubric. Of course, this is all about clarity.

A second step toward clarity is attending to content-related validity. This check for validity is about making sure we have adequately sampled from the content we taught. Content validity is easiest to understand when we talk about test creation. If a test is going to have 30 selected response questions (think multiple choice, true-false, matching) those 30 questions should proportionally represent time and investment spent on specific learning targets and performance indicators. For example, if three lessons were devoted to the long term learning target (LTLT), “I can evaluate reasons people migrate” and five lessons were devoted to the LTLT, “ I can evaluate the impact of migration on people and groups of people,” the corresponding assessment should sample from those LTLTs proportionally. In the case of our rubric example above, we can see that the items being sampled or assessed are claim, evidence, source-based argument, and reasoning. Similar to the case of sampling in the example of the test, we should conclude that since each of these items is represented in the rubric, they are proportionally sampled from what was taught.

The basic premise of accommodating, designing universally, and differentiating is that we peel away obstacles that might prevent learners from demonstrating what they have actually learned and that prevent us as assessors from seeing that clearly.

The final component of validity I’d like to discuss addresses equity of opportunity: Fairness. In checking our assessment tools for this component of validity, we need to consider a simple question and see the complexity inherent in that question: Does everyone have a fair opportunity to demonstrate their learning? We need to look at potential barriers like the assessment environment, language skills, access to resources, and learning abilities. Those barriers are often flagged for us with IEPs and 504 plans and as we get to know all of our students, we can more easily see barriers for any of our students that might not be formally flagged. The ideas I explored in Meeting the Range of Students’ Needs apply to our development of assessment too. The basic premise of accommodating, designing universally, and differentiating is that we peel away obstacles that might prevent learners from demonstrating what they have actually learned and that prevent us as assessors from seeing that clearly.

Striving for validity in our assessments is just one more step we can take to be as transparent as possible in our work. When we recall that the purpose of assessment is to determine what has been learned, we see that the creation of tools to accurately measure learning requires careful construction of those tools. They need to reflect the content accurately and they need to provide fair access to all learners. In short, our assessment tools need to be valid as we strive toward clarity and equity of opportunity.