This post provides a deeper look into the ideas of Learner Agency, one of JumpRope’s Core Values.

Student goal setting is one of the most powerful tools I have built into my practice. It is also one of the elements of teaching that seems to be the most elusive. As a former middle school classroom teacher and current lecturer at the university level, I have experienced and witnessed that building a practice of student goal setting demands that I take time to plan and launch the process, and support it in my classroom. This means I need to leave behind otherwise important content or processes to make time and space for student goal setting. Further, it requires that I find the balance point between choosing what I think each student needs to work on and supporting them in making informed choices for themselves. I need to invite them to examine their own data, help them understand what it means, and collaborate with them to fully understand where they are and where they might next go as learners. I continue to find, though, that this significant investment in time and focus yields real rewards for students.

I need to leave behind otherwise important content or processes to make time and space for student goal setting.

Decades of research on the topic of goal setting helps us see that students’ sense of agency, motivation, and achievement are all increased with the practice of effective goal setting (Cauley & McMillan, 2009). When students value their goals because they see them as relevant and worthy of pursuit, they are more likely to take steps toward attaining them (Turkay, 2014). And of course, as students see some success with goal attainment, they seek more success. It feels good to achieve a goal. As a guide for and collaborator with my students, part of my role in making sure they are setting effective goals is to continually help them see they are setting learning goals. These are based on our long term learning targets — the concepts, skills, and knowledge they are meant to attain through our work together. The act of supporting students through goal setting therefore demands that we are all clear on what those targets are and that as the teacher in the classroom, I continually provide equitable opportunities for my students to approach the targets in order to attain their goals.

As students see some success with goal attainment, they seek more success. It feels good to achieve a goal.

Beyond helping students see the content to consider in setting goals, we need to provide them with tools and strategies to frame and consider those goals. The work of organizational psychologists Edwin Locke and Gary Latham shows setting specific and challenging goals helps us in several important ways: It focuses attention on activities that will support goal attainment, elicits greater effort and persistence than low-challenging goals, and it encourages people to build from pre-existing knowledge and strategies to attain the goal (Locke and Latham, 2002). Their research reminds us of the SMART goal, a mechanism I use with my teaching interns each semester. As I work with them to write goals that are specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and timely, I coach them to establish the goal itself, the action steps they will take to attain the goal, and the assessment they will use to measure their progress with the goal. Younger learners might benefit from the simple elegance of the Next Steps Rubric (NSR) which helps them name what they have done well (stars), the success criteria (learning targets) and what to do next (stairs) (Stewart McCafferty & Beaudry, 110).

Data inquiry begins with establishing a culture where students feel safe to explore and even make mistakes.

Central to helping students set and work toward goals is supporting them in knowing how to examine and interpret learning data. In Leaders of Their Own Learning, Ron Berger lays out a comprehensive approach to this process. Like so many other steps in a transparent teaching practice, data inquiry begins with establishing a culture where students feel safe to explore and even make mistakes. Working from such a culture, we need to use examples to teach our students about data, help them see where and how it is used in fields they care about (sports, gaming, retail, medicine, etc.) One way to frame the exploration of data is in terms of whole class data. In courses with my graduate students, I share class performance data as a way to show students how I examine my own instruction to find the spots that need more attention.

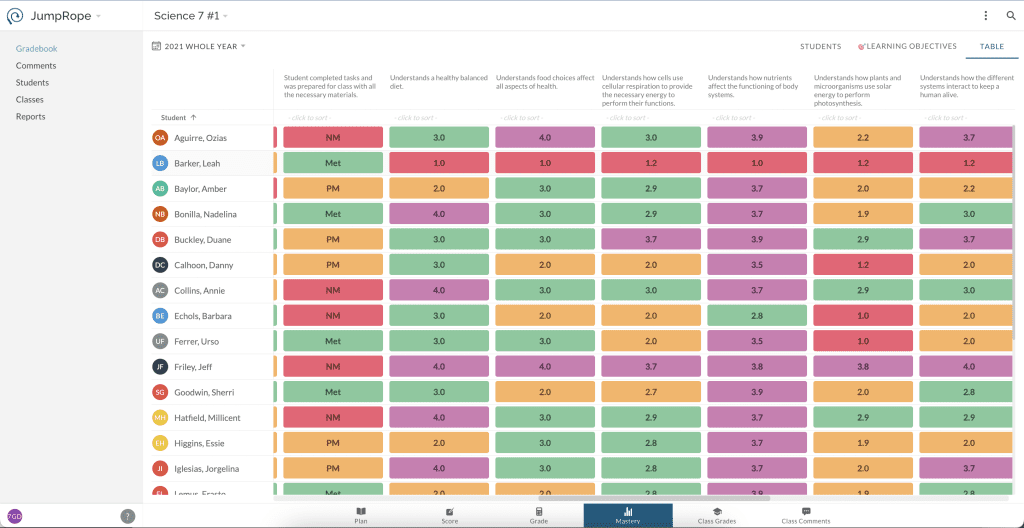

Class Mastery Report Table View

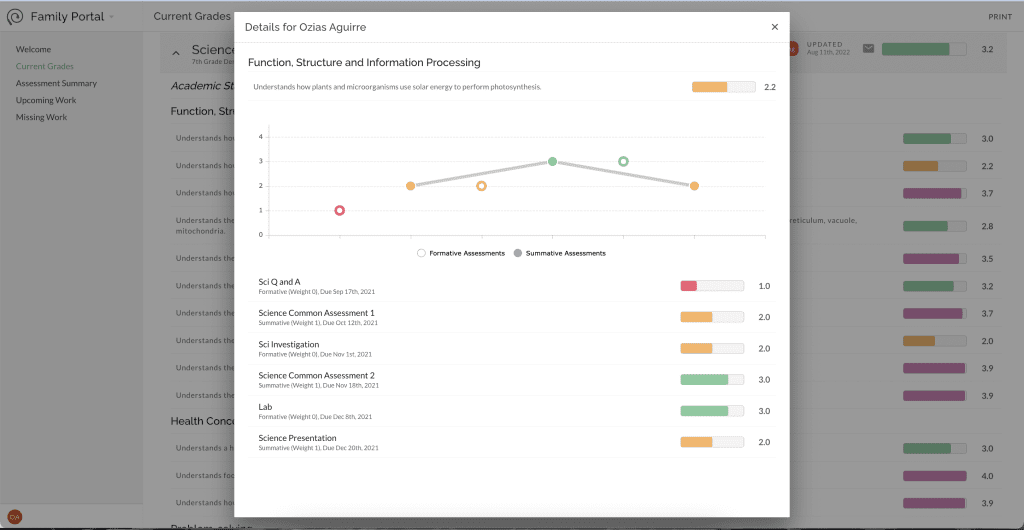

And finally, in coaching students to look at their own learning data, it’s important to help them see the areas where they have done well, both so they feel encouraged and also so they can build from their strengths to address the areas where they need to improve.

Individual Student Mastery Report

When students set goals for their learning, they enter into a contract with themselves. There are some steps we need to take in order to support them in moving toward fulfillment of that contract. These steps are simple in theory but they require us to carefully consider what we value in our classrooms. Supporting student goal setting demands that we provide students time, guidance, and resources. Teachers are masters of finding resources and offering guidance. Once we see student goal setting as a cornerstone of student agency, we can see that when we feel it’s not possible to add even one more minute to what we do in our classrooms, it really can and must be done.