This post provides a deeper look into the ideas of Clarity, one of JumpRope’s Core Values.

In assessing products or presentations, providing our students with an easily understood set of assessment expectations is an excellent way to help hold ourselves accountable and also guide them toward success. We might call that set of expectations a rubric, a scoring guide, success criteria, or something else. In any case, the simple fact of having it provides students with guideposts as they complete a project, write a paper, develop a presentation, or work on myriad other assignments. Creating such a set of expectations encourages us to consider what it is we’d like our students to demonstrate from their learning, and actually streamlines our work as we sit down to assess. Knowing precisely which criteria we are looking for focuses our attention and helps us resist the temptation to comment on or “correct” everything. And of course, simply having that set of expectations will help move us away from subjective assessment and begin to steer clear of our own biases. I will call the set of assessment expectations a rubric for the sake of ease in the rest of this post.

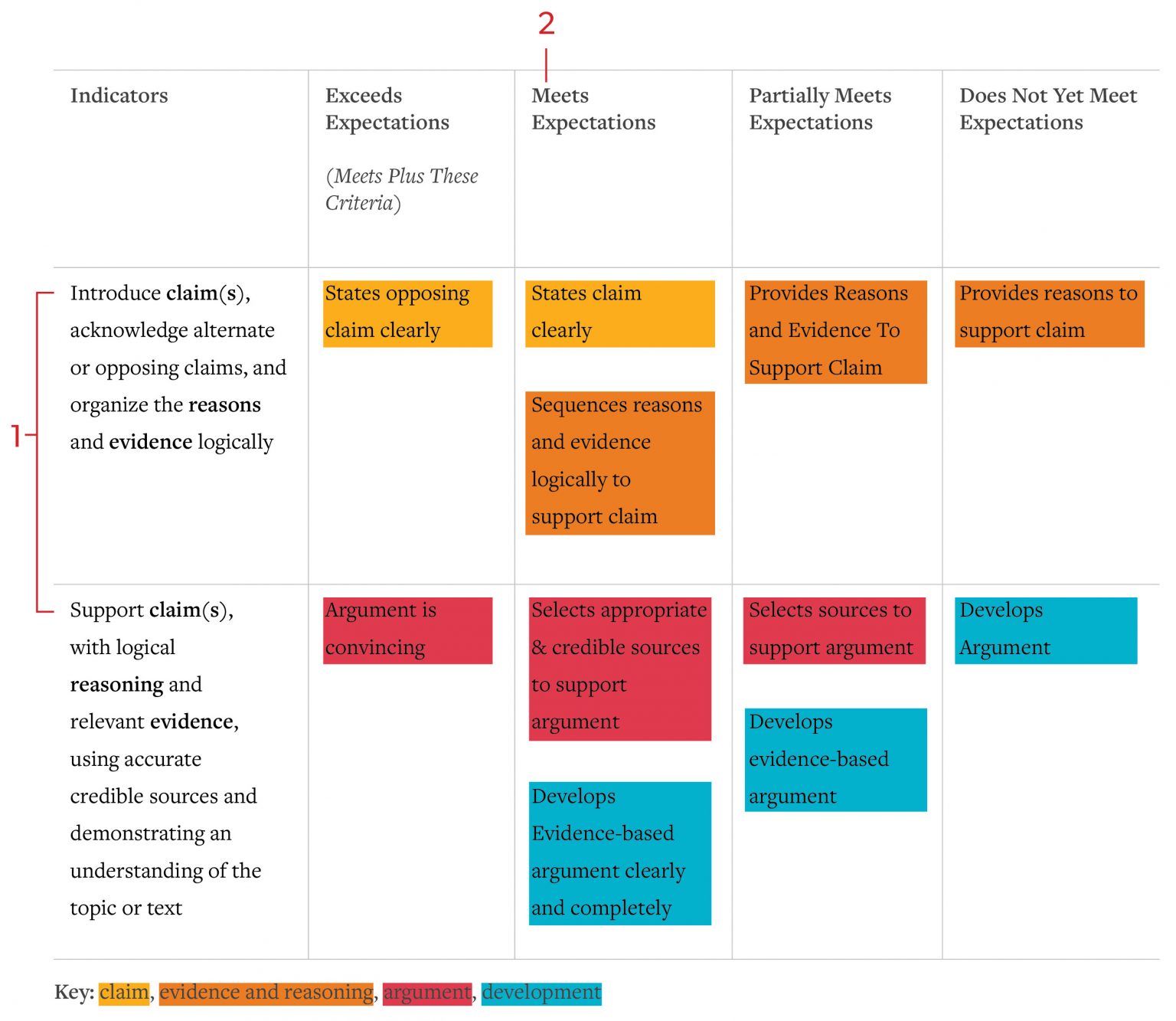

There are some concrete steps we should take in rubric development. The first, of course, is determining what the students are meant to learn. If the learning is procedural or conceptual in nature as opposed to factual, and if the demonstration of it will happen through extended writing, speaking, exhibiting a skill, or creating a product, a well-designed rubric will be a great help to both the students and the teacher. Part of zeroing in on what the students should learn is being able to name the performance indicator (PI) or long term learning target (LTLT) the assignment is meant to assess. It is reasonable for a single assignment to assess more than one PI or LTLT, but it’s important to avoid the kitchen sink model. For a refresher on PIs and LTLTs, take a look at Moving from Standards to targets. Think very carefully about the PI(s) or LTLT(s) you intend to assess: Will you actually teach these PIs or LTLTs prior to assessing them? Will you assess all components of those you have chosen or portions of them? Let’s look at an example from Common Core State Standards, 7th grade Writing. You will find this on p. 42 of the CCSS. In the example below, we see several choices to make in determining what to assess in a given instance. We might choose to focus initial instruction and therefore assessment on claim, reason, and evidence and subsequent instruction and assessment on the entirety of argument writing. See my earlier post on Assessment Mapping for a discussion on choosing to assess the entirety of a PI or LTLT or assessing only a portion of it.

EXAMPLE, COMMON CORE STANDARDS, 7th GRADE WRITING

1.Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence.

a. Introduce claim(s), acknowledge alternate or opposing claims, and organize the reasons and evidence logically.

b. Support claim(s) with logical reasoning and relevant evidence, using accurate, credible sources and demonstrating an understanding of the topic or text.

c. Use words, phrases, and clauses to create cohesion and clarify the relationships among claim(s), reasons, and evidence.

d. Establish and maintain a formal style.

e. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented.

Once you have figured out what you would like to assess (1 in image below), determine the rigor level at which you should assess (2 in image below). A note for JumpRope users here: in cases where you are working with the District Edition and have a school curated standards bank, your rigor levels have already been established. In this case, you might use those rigor levels verbatim for your rubric or you might derive from them assignment-specific language in creating a rubric. In thinking through rigor levels, I always turn to my trusted taxonomies to help me define precisely what it is I’d like my students to do as they demonstrate their learning. Some of my favorites are Bloom, Webb, and Marzano. I write the Meets Expectations column first, as that is the column indicating precisely what the students need to demonstrate. From there, you can determine Exceeds or Partially Meets, whichever feels easier to write in that moment. The goal is to look for different levels of thinking that all address the indicator or target. For more on developing the Exceeds column, take a look at this post.

Two cautions regarding rubric development: it is tempting to use language like, “always”, “mostly”, and “sometimes” or to specify quantities (like 3 paragraphs, or 2 sources, etc.) Try to keep in mind that we are assessing thinking. There are cases where quantity is what we are looking for, but always ask yourself if that is truly the case. As an example, in learning to find sources, if a student finds two highly relevant and reliable sources, for their research, their work is likely to be better than the student who finds four irrelevant or unreliable sources.

The example below is my attempt to show how I try to address varied levels of thinking in each column. Note that the columns describe what it is a student would include or do, not what they would omit or leave out.