Editor’s note: This post provides a deeper look into the ideas of Equity of Opportunity, one of JumpRope’s Core Values.

As teachers, we know that our antennae are always attuned to how well our students are doing. We also know that continuous data collection is not only burdensome, it’s not effective. In other words, weighing the pig won’t make it fatter. Forgive the analogy, but I think it works. We also know, however, that checking the pig’s weight, using the right scale at the right time, tells us if the pig is on pace to attain the weight it needs to win a blue ribbon at the county fair. And of course, once we arrive at the fair, the pig’s ultimate weight will be one variable in awarding that ribbon. If we look at classroom assessment as a measurement of learning, and we recognize that we are the facilitators of that learning, we can embrace the need to collect strategic and useful data toward and of that learning.

When I work with my students at the University of Southern Maine (USM) to help them design assessments and assessment systems, I talk about diagnostic, formative and summative assessment. I also talk about checks for understanding. I deliberately distinguish these types of assessments from one another so we share a common lexicon. The names we assign to these types of assessments ultimately are less important than understanding when and how to assess, and when and why to collect data.

The names we assign to these types of assessments ultimately are less important than understanding when and how to assess, and when and why to collect data.

Checks for understanding happen in-the-moment, while I am teaching. With my USM students, I distinguish between checks for directional understanding and checks for content understanding. Both are important, but our discussion here is focused on content. To check content understanding, I might pause 10 minutes into a full group lesson to ask some oral questions. Sometimes I listen in as students talk with one another, or watch as they complete cooperative or independent work. I might collect classwork such as note catchers, graphic organizers, problem sets, written responses, exit tickets, etc. The check can come during the class period or at the end of the class period if I know we will continue to build from the content we’ve addressed that day. The common thread for all of these checks for understanding is that I do not use them for formal data collection. I might offer a brief comment for some students, either in writing or orally, but offering feedback is not the goal. I might jot notes to myself if I hear or see some misunderstandings to address later or some good thinking I’d like a student to share with peers, but I am not keeping track of this information for the purposes of assessing learning. I am using these checks for understanding to refine my instruction that day and in the coming few days. To carry my clumsy analogy forward, I am simply eyeballing the pig here. No scale required.

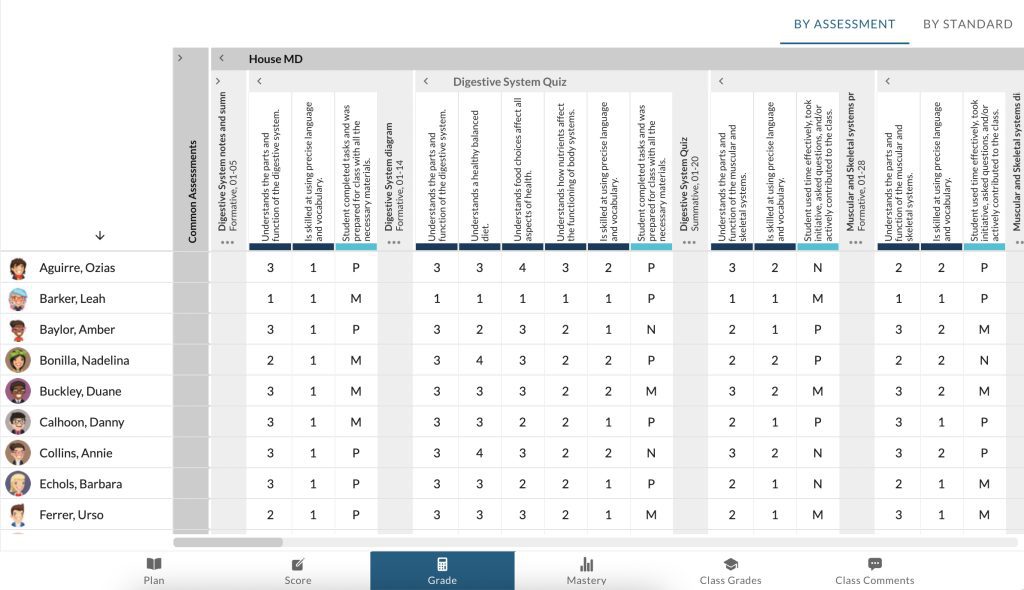

I do use some sort of scale, that is, I record data, when I assess diagnostically and formatively. For both types of assessment, I apply the same standards and scoring criteria I would to a summative assessment, though my diagnostic and formative assessments are never as comprehensive as a summative assessment would be. See below for an example of how this looks in my gradebook.

I feel it’s important to apply the same criteria so both my students and I see, relative to the ultimate goal, where they are at that moment. Unlike with checks for understanding, I collect and record these data for several reasons. First, like with checks for understanding, they help me make instructional decisions; things like how to group students and plan for differentiated lessons to address their various needs. Unlike the less formal checks for understanding, I use these formative assessments to inform my extended planning and to help students set learning goals. They serve as guideposts toward our summative targets and as such, help students and me chart a clear direction for learning. It’s important to note that these data never count toward students’ grades. The actual tools I use to collect these data might be the very same tools I use to check for understanding (oral communication, note catchers, graphic organizers, exit tickets) or they might be portions of summative assignments (essays, lab investigations, presentations, research papers, etc.) I especially like to formatively assess portions of summative assignments as students are in process to offer mid-course encouragement and guidance. I see formative assessments, above all others, as the type of assessment to accompany with critical feedback. Since offering feedback is time-consuming, I frequently employ techniques like collecting or observing student work on a rotational basis and training my students to offer peer feedback.

I see formative assessments, above all others, as the type of assessment to accompany with critical feedback.

Sometimes I can’t resist offering a brief comment on summative assignments, but unless those summative assignments have direct application toward a future assignment, or student performance on the summative is such that a student will need to revisit a portion of it, I try to limit the feedback I offer. After all, summative assessments are assessments of learning. They come at the natural end of some learning journey and so the feedback I might offer at this point likely is moot. Summative assessments are useful in knowing how well each student has done and how well a group of students has done with particular learning goals. Additionally, the data gives us insight into how successful our instruction was and can help us think about longer term or larger scale curriculum changes. For a bit more on that topic, look for a future post about using data to revise plans. I use the information I get from checks for understanding and formative assessments to guide my instruction as we approach summative assessments. Those data help me see how to prepare my students for success with the summative by revealing areas of instruction that need more attention and those where the students are on target. I don’t think of this sort of collection and application of data as “teaching to the test”, in part because so few of my assessments are actually tests, but also because I view this process as the transparency that accompanies preparing students for the demands of the summative assessment and helping them understand the goals therein. As a brief reminder, the best assessment systems include the use of a range of assessment methods. I still think of Rick Stiggins’ work as foundational in that realm.

Classroom assessment provides immeasurable value to our work with our students. The process of assessing provides us with easy entry points to see how well individual students and groups of students are progressing toward our learning goals.

Classroom assessment provides immeasurable value to our work with our students. The process of assessing provides us with easy entry points to see how well individual students and groups of students are progressing toward our learning goals. Classroom assessment helps us generate data that serves as fodder for discussion and goal setting with students. It also gives us information to adjust our instructional goals, the pace and format of our instruction, the way we group students, the strategies we apply, etc. to better help students learn. And of course, ultimately classroom assessment helps students and teachers see how well they have done in attaining learning goals. An important key to designing classroom assessments is knowing when and why we are assessing: when is it time to weigh the pig and what should we do with the results we see on the scale?